Identical particles

| Statistical mechanics |

|---|

| Thermodynamics · Kinetic theory |

Identical particles, or indistinguishable particles, are particles that cannot be distinguished from one another, even in principle. Species of identical particles include elementary particles such as electrons, and, with some clauses, composite particles such as atoms and molecules.[1]

There are two main categories of identical particles: bosons, which can share quantum states, and fermions, which do not share quantum states due to the Pauli exclusion principle. Examples of bosons are photons, gluons, phonons, and helium-4 atoms. Examples of fermions are electrons, neutrinos, quarks, protons and neutrons, and helium-3 atoms.

The fact that particles can be identical has important consequences in statistical mechanics. Calculations in statistical mechanics rely on probabilistic arguments, which are sensitive to whether or not the objects being studied are identical. As a result, identical particles exhibit markedly different statistical behavior from distinguishable particles. For example, the indistinguishability of particles has been proposed as a solution to Gibbs' mixing paradox.

Contents |

Distinguishing between particles

There are two ways in which one might distinguish between particles. The first method relies on differences in the particles' intrinsic physical properties, such as mass, electric charge, and spin. If differences exist, we can distinguish between the particles by measuring the relevant properties. However, it is an empirical fact that microscopic particles of the same species have completely equivalent physical properties. For instance, every electron in the universe has exactly the same electric charge; this is why we can speak of such a thing as "the charge of the electron".

Even if the particles have equivalent physical properties, there remains a second method for distinguishing between particles, which is to track the trajectory of each particle. As long as we can measure the position of each particle with infinite precision (even when the particles collide), there would be no ambiguity about which particle is which.

The problem with this approach is that it contradicts the principles of quantum mechanics. According to quantum theory, the particles do not possess definite positions during the periods between measurements. Instead, they are governed by wavefunctions that give the probability of finding a particle at each position. As time passes, the wavefunctions tend to spread out and overlap. Once this happens, it becomes impossible to determine, in a subsequent measurement, which of the particle positions correspond to those measured earlier. The particles are then said to be indistinguishable.

Quantum mechanical description of identical particles

Symmetrical and antisymmetrical states

We will now make the above discussion concrete, using the formalism developed in the article on the mathematical formulation of quantum mechanics.

Let n denote a complete set of (discrete) quantum numbers for specifying single-particle states (for example, for the particle in a box problem we can take n to be the quantized wave vector of the wavefunction.) For simplicity, consider a system composed of two identical particles. Suppose that one particle is in the state n1, and another is in the state n2. What is the quantum state of the system? Intuitively, it should be

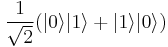

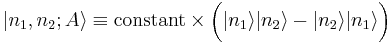

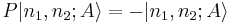

which is simply the canonical way of constructing a basis for a tensor product space  of the combined system from the individual spaces. However, this expression implies the ability to identify the particle with n1 as "particle 1" and the particle with n2 as "particle 2". If the particles are indistinguishable, this is impossible by definition; either particle can be in either state. It turns out, for reasons ultimately based in quantum field theory, that we must have:

of the combined system from the individual spaces. However, this expression implies the ability to identify the particle with n1 as "particle 1" and the particle with n2 as "particle 2". If the particles are indistinguishable, this is impossible by definition; either particle can be in either state. It turns out, for reasons ultimately based in quantum field theory, that we must have:

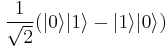

States where this is a sum are known as symmetric; states involving the difference are called antisymmetric. More completely, symmetric states have the form

while antisymmetric states have the form

Note that if n1 and n2 are the same, the antisymmetric expression gives zero, which cannot be a state vector as it cannot be normalized. In other words, in an antisymmetric state two identical particles cannot occupy the same single-particle states. This is known as the Pauli exclusion principle, and it is the fundamental reason behind the chemical properties of atoms and the stability of matter.

Exchange symmetry

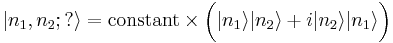

The importance of symmetric and antisymmetric states is ultimately based on empirical evidence. It appears to be a fact of nature that identical particles do not occupy states of a mixed symmetry, such as

There is actually an exception to this rule, which we will discuss later. On the other hand, we can show that the symmetric and antisymmetric states are in a sense special, by examining a particular symmetry of the multiple-particle states known as exchange symmetry.

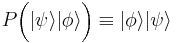

Let us define a linear operator P, called the exchange operator. When it acts on a tensor product of two state vectors, it exchanges the values of the state vectors:

P is both Hermitian and unitary. Because it is unitary, we can regard it as a symmetry operator. We can describe this symmetry as the symmetry under the exchange of labels attached to the particles (i.e., to the single-particle Hilbert spaces).

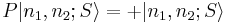

Clearly, P² = 1 (the identity operator), so the eigenvalues of P are +1 and −1. The corresponding eigenvectors are the symmetric and antisymmetric states:

In other words, symmetric and antisymmetric states are essentially unchanged under the exchange of particle labels: they are only multiplied by a factor of +1 or −1, rather than being "rotated" somewhere else in the Hilbert space. This indicates that the particle labels have no physical meaning, in agreement with our earlier discussion on indistinguishability.

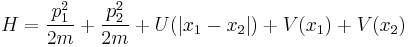

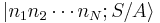

We have mentioned that P is Hermitian. As a result, it can be regarded as an observable of the system, which means that we can, in principle, perform a measurement to find out if a state is symmetric or antisymmetric. Furthermore, the equivalence of the particles indicates that the Hamiltonian can be written in a symmetrical form, such as

It is possible to show that such Hamiltonians satisfy the commutation relation

According to the Heisenberg equation, this means that the value of P is a constant of motion. If the quantum state is initially symmetric (antisymmetric), it will remain symmetric (antisymmetric) as the system evolves. Mathematically, this says that the state vector is confined to one of the two eigenspaces of P, and is not allowed to range over the entire Hilbert space. Thus, we might as well treat that eigenspace as the actual Hilbert space of the system. This is the idea behind the definition of Fock space.

Fermions and bosons

The choice of symmetry or antisymmetry is determined by the species of particle. For example, we must always use symmetric states when describing photons or helium-4 atoms, and antisymmetric states when describing electrons or protons.

Particles which exhibit symmetric states are called bosons. As we will see, the nature of symmetric states has important consequences for the statistical properties of systems composed of many identical bosons. These statistical properties are described as Bose–Einstein statistics.

Particles which exhibit antisymmetric states are called fermions. As we have seen, antisymmetry gives rise to the Pauli exclusion principle, which forbids identical fermions from sharing the same quantum state. Systems of many identical fermions are described by Fermi–Dirac statistics.

Parastatistics are also possible.

In certain two-dimensional systems, mixed symmetry can occur. These exotic particles are known as anyons, and they obey fractional statistics. Experimental evidence for the existence of anyons exists in the fractional quantum Hall effect, a phenomenon observed in the two-dimensional electron gases that form the inversion layer of MOSFETs. There is another type of statistic, known as braid statistics, which are associated with particles known as plektons.

The spin-statistics theorem relates the exchange symmetry of identical particles to their spin. It states that bosons have integer spin, and fermions have half-integer spin. Anyons possess fractional spin.

N particles

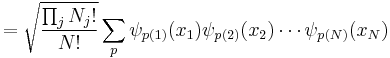

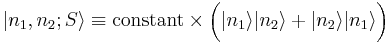

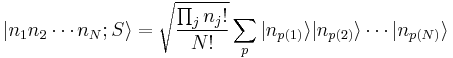

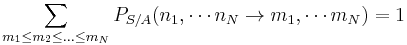

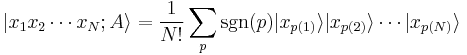

The above discussion generalizes readily to the case of N particles. Suppose we have N particles with quantum numbers n1, n2, ..., nN. If the particles are bosons, they occupy a totally symmetric state, which is symmetric under the exchange of any two particle labels:

Here, the sum is taken over all different states under permutations p acting on N elements. The square root left to the sum is a normalizing constant. The quantity nj stands for the number of times each of the single-particle states appears in the N-particle state.

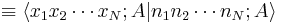

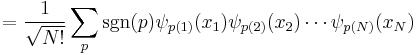

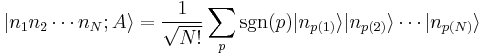

In the same vein, fermions occupy totally antisymmetric states:

Here, sgn(p) is the signature of each permutation (i.e. +1 if p is composed of an even number of transpositions, and −1 if odd.) Note that we have omitted the Πjnj term, because each single-particle state can appear only once in a fermionic state. Otherwise the sum would again be zero due to the antisymmetry, thus representing a physically impossible state. This is the Pauli exclusion principle for many particles.

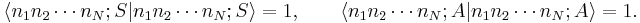

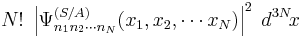

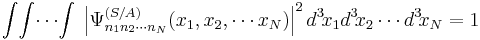

These states have been normalized so that

Measurements of identical particles

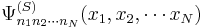

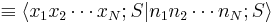

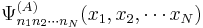

Suppose we have a system of N bosons (fermions) in the symmetric (antisymmetric) state

and we perform a measurement of some other set of discrete observables, m. In general, this would yield some result m1 for one particle, m2 for another particle, and so forth. If the particles are bosons (fermions), the state after the measurement must remain symmetric (antisymmetric), i.e.

The probability of obtaining a particular result for the m measurement is

We can show that

which verifies that the total probability is 1. Note that we have to restrict the sum to ordered values of m1, ..., mN to ensure that we do not count each multi-particle state more than once.

Wavefunction representation

So far, we have worked with discrete observables. We will now extend the discussion to continuous observables, such as the position x.

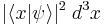

Recall that an eigenstate of a continuous observable represents an infinitesimal range of values of the observable, not a single value as with discrete observables. For instance, if a particle is in a state |ψ⟩, the probability of finding it in a region of volume d3x surrounding some position x is

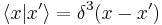

As a result, the continuous eigenstates |x⟩ are normalized to the delta function instead of unity:

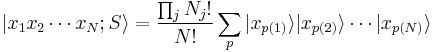

We can construct symmetric and antisymmetric multi-particle states out of continuous eigenstates in the same way as before. However, it is customary to use a different normalizing constant:

We can then write a many-body wavefunction,

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

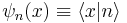

where the single-particle wavefunctions are defined, as usual, by

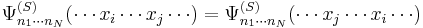

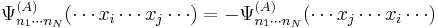

The most important property of these wavefunctions is that exchanging any two of the coordinate variables changes the wavefunction by only a plus or minus sign. This is the manifestation of symmetry and antisymmetry in the wavefunction representation:

The many-body wavefunction has the following significance: if the system is initially in a state with quantum numbers n1, ..., nN, and we perform a position measurement, the probability of finding particles in infinitesimal volumes near x1, x2, ..., xN is

The factor of N! comes from our normalizing constant, which has been chosen so that, by analogy with single-particle wavefunctions,

Because each integral runs over all possible values of x, each multi-particle state appears N! times in the integral. In other words, the probability associated with each event is evenly distributed across N! equivalent points in the integral space. Because it is usually more convenient to work with unrestricted integrals than restricted ones, we have chosen our normalizing constant to reflect this.

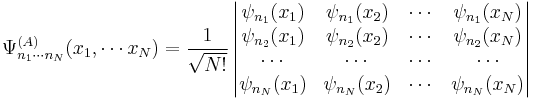

Finally, it is interesting to note that antisymmetric wavefunction can be written as the determinant of a matrix, known as a Slater determinant:

Statistical properties

Statistical effects of indistinguishability

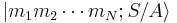

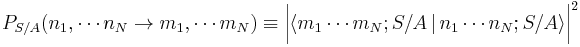

The indistinguishability of particles has a profound effect on their statistical properties. To illustrate this, let us consider a system of N distinguishable, non-interacting particles. Once again, let nj denote the state (i.e. quantum numbers) of particle j. If the particles have the same physical properties, the nj's run over the same range of values. Let ε(n) denote the energy of a particle in state n. As the particles do not interact, the total energy of the system is the sum of the single-particle energies. The partition function of the system is

where k is Boltzmann's constant and T is the temperature. We can factor this expression to obtain

where

If the particles are identical, this equation is incorrect. Consider a state of the system, described by the single particle states [n1, ..., nN]. In the equation for Z, every possible permutation of the n's occurs once in the sum, even though each of these permutations is describing the same multi-particle state. We have thus over-counted the actual number of states.

If we neglect the possibility of overlapping states, which is valid if the temperature is high, then the number of times we count each state is approximately N!. The correct partition function is

Note that this "high temperature" approximation does not distinguish between fermions and bosons.

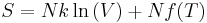

The discrepancy in the partition functions of distinguishable and indistinguishable particles was known as far back as the 19th century, before the advent of quantum mechanics. It leads to a difficulty known as the Gibbs paradox. Gibbs showed that if we use the equation Z = ξN, the entropy of a classical ideal gas is

where V is the volume of the gas and f is some function of T alone. The problem with this result is that S is not extensive – if we double N and V, S does not double accordingly. Such a system does not obey the postulates of thermodynamics.

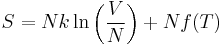

Gibbs also showed that using Z = ξN/N! alters the result to

which is perfectly extensive. However, the reason for this correction to the partition function remained obscure until the discovery of quantum mechanics.

Statistical properties of bosons and fermions

There are important differences between the statistical behavior of bosons and fermions, which are described by Bose–Einstein statistics and Fermi–Dirac statistics respectively. Roughly speaking, bosons have a tendency to clump into the same quantum state, which underlies phenomena such as the laser, Bose–Einstein condensation, and superfluidity. Fermions, on the other hand, are forbidden from sharing quantum states, giving rise to systems such as the Fermi gas. This is known as the Pauli Exclusion Principle, and is responsible for much of chemistry, since the electrons in an atom (fermions) successively fill the many states within shells rather than all lying in the same lowest energy state.

We can illustrate the differences between the statistical behavior of fermions, bosons, and distinguishable particles using a system of two particles. Let us call the particles A and B. Each particle can exist in two possible states, labelled  and

and  , which have the same energy.

, which have the same energy.

We let the composite system evolve in time, interacting with a noisy environment. Because the  and

and  states are energetically equivalent, neither state is favored, so this process has the effect of randomizing the states. (This is discussed in the article on quantum entanglement.) After some time, the composite system will have an equal probability of occupying each of the states available to it. We then measure the particle states.

states are energetically equivalent, neither state is favored, so this process has the effect of randomizing the states. (This is discussed in the article on quantum entanglement.) After some time, the composite system will have an equal probability of occupying each of the states available to it. We then measure the particle states.

If A and B are distinguishable particles, then the composite system has four distinct states:  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  . The probability of obtaining two particles in the

. The probability of obtaining two particles in the  state is 0.25; the probability of obtaining two particles in the

state is 0.25; the probability of obtaining two particles in the  state is 0.25; and the probability of obtaining one particle in the

state is 0.25; and the probability of obtaining one particle in the  state and the other in the

state and the other in the  state is 0.5.

state is 0.5.

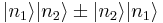

If A and B are identical bosons, then the composite system has only three distinct states:  ,

,  , and

, and  . When we perform the experiment, the probability of obtaining two particles in the

. When we perform the experiment, the probability of obtaining two particles in the  state is now 0.33; the probability of obtaining two particles in the

state is now 0.33; the probability of obtaining two particles in the  state is 0.33; and the probability of obtaining one particle in the

state is 0.33; and the probability of obtaining one particle in the  state and the other in the

state and the other in the  state is 0.33. Note that the probability of finding particles in the same state is relatively larger than in the distinguishable case. This demonstrates the tendency of bosons to "clump."

state is 0.33. Note that the probability of finding particles in the same state is relatively larger than in the distinguishable case. This demonstrates the tendency of bosons to "clump."

If A and B are identical fermions, there is only one state available to the composite system: the totally antisymmetric state  . When we perform the experiment, we inevitably find that one particle is in the

. When we perform the experiment, we inevitably find that one particle is in the  state and the other is in the

state and the other is in the  state.

state.

The results are summarized in Table 1:

| Particles | Both 0 | Both 1 | One 0 and one 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distinguishable | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| Bosons | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.33 |

| Fermions | 0 | 0 | 1 |

As can be seen, even a system of two particles exhibits different statistical behaviors between distinguishable particles, bosons, and fermions. In the articles on Fermi–Dirac statistics and Bose–Einstein statistics, these principles are extended to large number of particles, with qualitatively similar results.

The homotopy class

To understand why we have the statistics that we do for particles, we first have to note that particles are point localized excitations and that particles that are spacelike separated do not interact. In a flat d-dimensional space M, at any given time, the configuration of two identical particles can be specified as an element of M × M. If there is no overlap between the particles, so that they do not interact (at the same time, we are not referring to time delayed interactions here, which are mediated at the speed of light or slower), then we are dealing with the space [M × M]/{coincident points}, the subspace with coincident points removed. (x, y) describes the configuration with particle I at x and particle II at y. (y, x) describes the interchanged configuration. With identical particles, the state described by (x, y) ought to be indistinguishable (which ISN'T the same thing as identical!) from the state described by (y, x). Let's look at the homotopy class of continuous paths from (x, y) to (y, x). If M is Rd where d ≥ 3, then this homotopy class only has one element. If M is R2, then this homotopy class has countably many elements (i.e. a counterclockwise interchange by half a turn, a counterclockwise interchange by one and a half turns, two and a half turns, etc., a clockwise interchange by half a turn, etc.). In particular, a counterclockwise interchange by half a turn is NOT homotopic to a clockwise interchange by half a turn. Lastly, if M is R, then this homotopy class is empty. Obviously, if M is not isomorphic to Rd, we can have more complicated homotopy classes...

What does this all mean?

Let's first look at the case d ≥ 3. The universal covering space of [M × M]/{coincident points}, which is none other than [M × M]/{coincident points} itself, only has two points which are physically indistinguishable from (x, y), namely (x, y) itself and (y, x). So, the only permissible interchange is to swap both particles. Performing this interchange twice gives us (x, y) back again. If this interchange results in a multiplication by +1, then we have Bose statistics and if this interchange results in a multiplication by −1, we have Fermi statistics.

Now how about R2? The universal covering space of [M × M]/{coincident points} has infinitely many points that are physically indistinguishable from (x, y). This is described by the infinite cyclic group generated by making a counterclockwise half-turn interchange. Unlike the previous case, performing this interchange twice in a row does not lead us back to the original state. So, such an interchange can generically result in a multiplication by exp(iθ) (its absolute value is 1 because of unitarity...). This is called anyonic statistics. In fact, even with two DISTINGUISHABLE particles, even though (x, y) is now physically distinguishable from (y, x), if we go over to the universal covering space, we still end up with infinitely many points which are physically indistinguishable from the original point and the interchanges are generated by a counterclockwise rotation by one full turn which results in a multiplication by exp(iφ). This phase factor here is called the mutual statistics.

As for R, even if particle I and particle II are identical, we can always distinguish between them by the labels "the particle on the left" and "the particle on the right". There is no interchange symmetry here and such particles are called plektons.

The generalization to n identical particles doesn't give us anything qualitatively new because they are generated from the exchanges of two identical particles.

See also

Footnotes

- ^ The definition of identical composite particles depends on what exactly we consider as a composite particle, because they have more intrinsic degrees of freedom (i.e. quantum numbers) than elementary particles have. If we neglect, for example, transitions between atomic energy levels and consider only a specific one such as an atom's ground state, then multiple atoms must all be in that state to be identical.

![\left[P, H\right] = 0](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/f08334470b180652447bdca572528d64.png)

![Z = \sum_{n_1, n_2, \cdots n_N} \exp\left\{ -\frac{1}{kT} \left[ \epsilon(n_1) %2B \epsilon(n_2) %2B \cdots \epsilon(n_N) \right] \right\}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/d7a89cc7ab4b4c22964ed43d9d9e4756.png)

![\xi = \sum_n \exp\left[ - \frac{\epsilon(n)}{kT} \right].](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/e9bcf03de111b5f8e6912f6de9a13096.png)